The Mechanics of Unbundling Part IV - The Framework and Predictions

A Deep Dive Into how Horizontal Platforms Truly Become Unbundled.

Welcome Back

This article marks the final installment of the four-part series on how digital platforms become unbundled. For those interested in Part I, II, or III, they can be found here:

- Part I - Carrying Capacity

- Part II - Platform Dimensionality

- Part III - Network Effects Type & Strength

- Part IV - The Framework & Predictions

Harry’s tweet on the unbundling of LinkedIn sparked thoughtful debate between both sides.

“The Unbundling of LinkedIn will create 20+ companies worth $5B+.

Heavily segmented, heavily veticalised, with highly specific functionality for each vertical.

Let the unbundling of LinkedIn begin….”

- Harry Stebbings

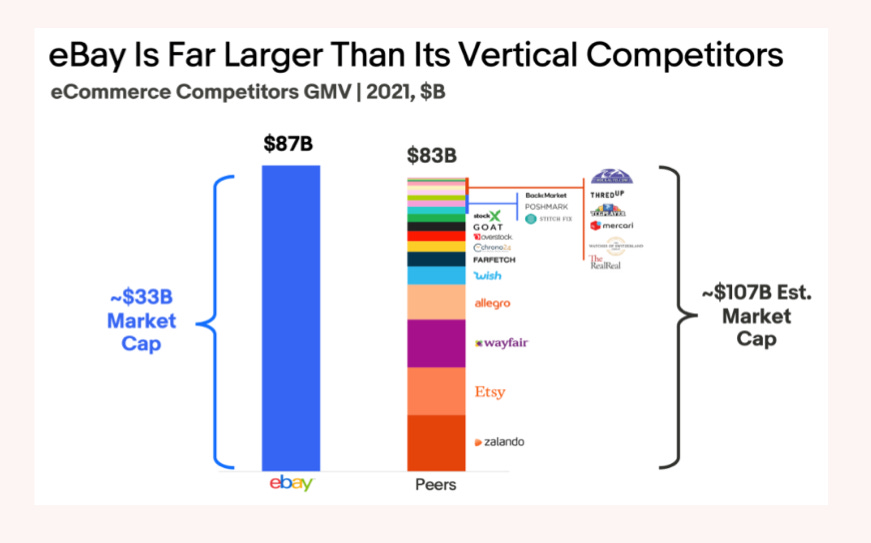

To understand which side we stood on, we retraced the footprints of history and analyzed horizontal platforms such as Craigslist, eBay, and Uber, which exposed initial surprises. eBay, despite its perceived position in the market, is still larger than all of its vertical rivals combined.

*Image from eBay’s annual investor report

And, Craigslist, which has grown 5x since 2010, is still thriving in rural states. (More from Part I if you care to learn more)

Answering "why?" to these questions revealed a set of foundational principles that we will use to better understand how secure incumbent platforms are from vertical competition and the financial benefit they will enjoy by leveraging supply-side economies of scale.

Distilled to its most simplistic form, the quantity, variety, and strength of a platform's network and its subnetworks indicate how at risk it might be to face vertical competition. The Holy Grail of platforms possesses a singular, homogenous network with high barriers to entry (indicating a strong network).

In reality, this is rarely the case. Most platforms have a chink in their armor and fall down in at least one of these areas providing an opportunity for competition. These characteristics are not created equally, though.

Applying the framework mentioned above to the platforms that we've discussed throughout the three parts thus far, we will posit the order of platforms that we've analyzed throughout the series likely to face vertical competition from most likely to least likely:

Craigslist

Food Delivery Businesses

Ride Share

eBay

LinkedIn

Airbnb

YouTube

Google Search

These platforms can be plotted on a three-dimensional matrix relative to one another using the characteristics we’ve discussed.

Let’s build this matrix.

Local Versus Global Networks (Quantity)

The first vector is rooted in understanding, by definition, how many sub-networks a platform possesses. Platforms and marketplaces fall into one of two camps - They are either global or local in nature.

Local network effect - A network whose suppliers only derive value from demand localized to specific geography. Doordash, Craigslist, Tinder, Fixer, etc.

Global network effect - A network whose suppliers find value from demand independent of location. eBay, Airbnb, Reddit, Goat, Poshmark, etc.

Businesses that exhibit local network effects are more susceptible to challengers due to the sheer quantity of networks that they must defend. Each network is unique and doesn't benefit from the other geographies' demand or supply-side scale advantage. For example, drivers on Uber's platform in Miami are not concerned about the riders in Chicago. The value is inherently localized and isolated from one another.

In contrast, supply and demand create a symbiotic relationship for businesses that exhibit global network effects independent of location. This geo-independent relationship creates a denser network, as the supply and demand are not clustered and isolated but rather compound on one another. Even in the case of Airbnb, hosts are concerned not only about the density of listings in their local geographic area but also about the awareness of the marketplace in popular travel destinations as a whole. Optionality increases the number of travelers attracted to the platform, making Airbnb even more attractive for hosts.

Platforms confined by geo are more capital-intensive to start and lend themselves to city-by-city warfare, as exhibited by the food delivery and rideshare wars.

(More detail on this in Part III)

Platform Heterogeneity (Variety)

For a platform that exhibits local network effects, the quantity of subnetworks scales as the number of geographies it serves. However, global platforms can (obviously) be fragmented in nature, too. Thus, our framework must extend beyond the type of network effect to account for this fragmentation.

Broadly speaking, heterogeneous platforms across the types of transactions they facilitate and the use cases they service will lend themselves to niches and subnetworks.

Signals that a platform may be heterogeneous across types of transactions is if they differ across the following characteristics:

Authenticity/Quality - Is there skepticism that the product could be fake or not to the buyer's expected quality? Examples could be phony inventory, poor work quality in a purchased professional service, etc. Building features to establish consumer trust is often no easy feat.

Price - Is the price dynamic? Does it depend on other suppliers? Appropriate pricing is crucial for suppliers to quickly maximize their income and turn inventory. Examples include cars, tickets, and homes.

Fragmentation & The uniqueness of Supply - How many unique units of supply are available? Unique supply is often challenging to acquire but important to consumers.

Discoverability/Time to value - How challenging is it to build features that allow users to find what they’re looking for? Examples include unique taxonomies/or granular search, date ranges, and maps in the case of looking for rentals, qualifications for professional services, etc.

Alternative Services - Are other services required to complete the transaction? Examples could be delivery, financing the purchase, or human intervention.

Catering to transactions that vary across these characteristics becomes increasingly complex as a business scales (for further analysis, read part II).

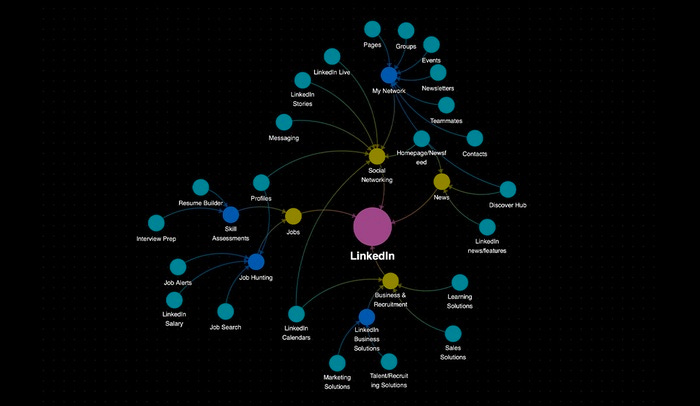

Understanding heterogeneity across use cases is more straightforward to understand but more complex to measure. For example, across LinkedIn’s four major services: Business & Recruitment, Jobs, News, and Social Networking, it’s unclear how many users solely utilize one service or a sub-service within that service forming a subnetwork that can be splintered off to breed loyal behavior.

*Image courtesy of businessofbusiness.com

Understanding such behavior is critical, though. The more isolated a particular sub-network is, i.e., the more the sub-network only comes to the platform to perform that specific use case or consume a certain type of supply, the more likely a user would potentially leave the incumbent parent network altogether in favor of a vertical challenger that better suits their needs, greatly enhancing the probability of success.

Adding our second characteristic, a matrix takes shape:

As alluded to above, getting an accurate grasp on how heterogeneous a platform is without engagement data is challenging, and a platform's position on this matrix is subjective without it. With significant overlap across use cases/types of supply, a vertical challenger providing a better alternative may not actually unbundle the incumbent but supplement it.

The ideal position for a platform is to be in the top right-hand corner of the matrix, a homogenous platform that exhibits global network effects. Those in the bottom left-hand corner are the most prone to facing vertical competition; Local platforms are highly heterogeneous.

Network Effect Strength (Strength)

The matrix may mislead us, though. Uber and Doordash are not as similar businesses as the matrix suggests. The intensity of competition is also variable across businesses that exhibit each type of network effect. Food delivery and ride share are both categorized as local network effect categories of businesses. Yet, I would argue that the barriers to entry in rideshare are higher, and the advantage of scale is stronger than that of food delivery. Thus, our framework must include a final dimension to account for this differentiation.

To complete the picture of how intense the competition will be for local and global network effects businesses, we must understand how strong of a network effect the incumbent possesses and how likely it is to ward off competitors. I.e., what minimally viable service or product must a competitor offer to breed liquidity? The lower this threshold is, the lower the barrier to entry for potential competitors.

Determining this threshold is more straightforward in some cases than others.

For rideshare businesses, consumer considerations are dominated by price and the ability to quickly attain a ride (Uber estimates this to be 3-5 minutes). Therefore, bolstering the supply side to a level that delivers rides faster is unnecessary and doesn't provide additional value to the user.

In addition, because the supply side in rideshare is homogenous, consumers are less loyal as rides are seen as indistinguishable from one another. The interchangeability between drivers among riders and vice versa ultimately means that a platform can keep both sides captive is less likely.

According to the rideshareguy, “83.5% of drivers surveyed work for multiple rideshare apps. For consumers, checking multiple rideshare apps is a common ritual before booking a trip.

The lower barriers reinforce the number of companies we see competing. Any service that can attract enough drivers to provide a comparable level of service will be competitive in the market. The result is competitive threats at a regional and local level vying for market share.

Appending this characteristic to our matrix results in the following three-dimensional space.

Without complete data on how heterogeneous a platform is and, to some extent, what the hurdle rate is to provide a minimally viable alternative to compete in a given market, placing these platforms is a bit like shooting from the hip. The debate around the exact placement of these platforms is hardly relevant, though. The key takeaway is that the further along a startup is along the red (quantity), blue (variety), and green (strength) axis, the more defensible and less prone it is to face vertical competition.

Wrapping up & Predictions

It's important to note that because startups are dynamic in nature, their location within the three-dimensional framework is likely to shift over time. As platforms saturate their initial market, they begin to bundle additional product features (as is the case with LinkedIn in corporate learning, recruitment, etc.), and unexpected behavior starts to form (as is the case in Facebook communities). Each case results in subnetworks forming, which puts the platform at risk.

Jeff Jordan and D’Arcy Coolican summarize it best:

“The moral of the story is this: In all but a few circumstances, the broad horizontal verticals eventually break. They become a victim of their own success. As the platforms grow, their submarkets grow too; their product gets pulled in a million different directions. Users get annoyed with an experience and business that caters to the lowest common denominator. And suddenly, what was previously too small a market to care about is a very interesting place for a standalone newco. Like clockwork, a new wave of innovation begins to swell, picking off the compelling verticals the new horizontal players cannot satisfy.”

Platforms with isolated sub-networks that solely depend on the parent network for that specific use case or type of transaction are the most at risk for unbundling. For example, Craigslist with home rentals. The emergence of Airbnb caused Craigslist’s short-term rental market to virtually go to 0. Providing a superior alternative splinters users from the incumbent and breeds loyalty on the emerging, vertical platform. Without captivity, the advantages of supply-side scale cannot truly be reaped as they have been with Airbnb and homes or YouTube and videos.

Identifying and vertically integrating such subnetworks is the path of least resistance for founders starting businesses and investors looking for new opportunities to deploy capital.

To accurately answer whether or not LinkedIn will see its platform splintered and whether users loyally opt for a vertical solution could only truly be justified by seeing engagement data across the platform. This data would indicate how many sub-networks it truly possesses.

That said, we can draw a rough conclusion.

Most arguments as to why LinkedIn will be pulled apart revolve around the fact that LinkedIn lacks industry specific features. I.e. real estate agents have different needs than engineers who have different needs accountants etc. This argument discounts the overlap between whatever this specific functionality is and the fundamental value that LinkedIn provides: The ability to reach professionals across specific industries. This is industry agnostic web is principally where LinkedIn derives its value, whether that’s networking, sales, or recruiting.

From the outside looking in, we can draw a corollary between our analysis of local and global networks to understand the value of LinkedIn’s monolithic network. A localized network in which professionals are solely relegated to an industry-specific platform would eliminate the ability to connect with others outside their ecosystem. Accountants may want to connect with those in law, those in law may want to network with those in tech, and so on.

Businesses are able to find value through an individual user’s inherent usage of the platform similar to how an advertiser does on Instagram. Solely by engaging with the platform for news, networking & messaging, or even updating your job title, allows enterprises to recruit candidates when they’re not looking for jobs, marketers to push their product to the appropriate buyer, and salesmen to target the right person in an organization.

LinkedIn has become the system of record where users are publicly available, an experience that is challenging to replicate.

In addition, from a performance perspective, the business has also been doing quite well. LinkedIn has grown revenue 5x over the past 5 years with little signs of slowing down.

*Source - Statista

Although the network is alive and well, and the argument has been made that LinkedIn will be difficult to displace, it’s not to say that opportunities do not and will not exist. To repeat Jeff Jordan and D’Arcy Coolican: All horizontal platforms eventually break.

Until a platform can provide similar value to users to work across industries, I believe we’re bound to see products that solve users’ problems deeper than LinkedIn currently does, but they will more likely than not be supplemental and exist alongside the platform rather than pull users away from LinkedIn altogether.

It’s also likely that we see products serve segments that LinkedIn never addressed in the first place, such as blue-collar workers. A network that never existed on the incumbent to begin with, though, is not unbundling. It would be the equivalent of saying YouTube unbundled Google.

Ultimately, it’s the founder's insight that recognizes the ripe sub-network within the large parent to unbundle. I’m continually fascinated to see how founders are attacking and building marketplaces, and if you’re building one of these networks, I’d love to chat.